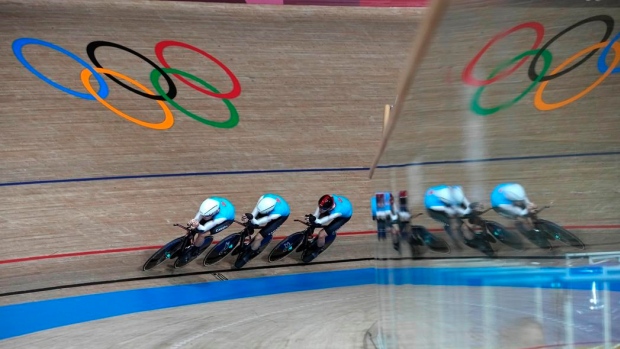

Canadian track cycling already reaping rewards of Pan Am velodrome at Tokyo Games

TOKYO — Canada’s track cyclists used to constantly be on the move.

A country without a permanent velodrome, the best of the best were forced to crisscross the globe to develop, train and compete.

The results on the international stage were still there despite the lack of infrastructure — Canadian riders won seven Olympic medals between 1984 and 2016 — but the transient lifestyle was draining on both athletes and the program’s coffers.

“We really had a nomadic squad,” Cycling Canada high performance director Kris Westwood said. “What we could do was was really limited.

“We’d identify (prospects) and then take them to L.A. to train there … or some other velodrome somewhere in the world.”

The 2015 Pan American Games in Toronto changed everything.

A year-round, world-class facility some 50 kilometres west of Canada’s biggest city in the town of Milton, Ont., is part of that summer sporting showcase’s legacy.

“It’s been transformational,” Westwood continued. “Now we can actually work with the athletes over a longer period of time, have the development riders working alongside the elite riders, do coach development, have all the sports science staff in the same building.

“You can’t run a program without that type of facility. For us, it’s meant a huge step up.”

And it’s having an impact at the Tokyo Games just six years later.

Canada sent its largest cycling team to Japan, with 12 competing on the track this week, including Milton product Michael Foley. The 22-year-old joined up in his hometown and quickly moved to the provincial and national teams.

“Without the track there, maybe he wouldn’t be at the Olympics,” Westwood said. “We have the biggest (Canadian) Olympic cycling team in history.

“And that is 99 per cent thanks to the Milton velodrome.”

Westwood said seeing that success this soon only reinforces the venue’s importance.

“It’s huge,” he said. “We weren’t expecting to see it really bear fruit for eight to 10 years.”

Apart from Foley, Canada’s other track cyclists competing in the city of Izu, about 130 kilometres southwest of Tokyo, are Allison Beveridge, Annie Foreman-Mackey, Ariane Bonhomme, Derek Gee, Georgia Simmerling, Hugo Barrette, Jasmin Duehring, Jay Lamoureux, Kelsey Mitchell, Lauriane Genest, Nick Wammes and Vincent De Haître.

Simmerling, Duehring and Beveridge were part of the group that won bronze in women’s team pursuit at the 2016 Rio Games. Duehring also helped Canada finish third in the same event four years earlier in London.

Curt Harnett, the country’s most decorated Olympic cyclist with three medals, including back-to-back bronze performances in 1992 and 1996, said in an interview before the COVID-19 pandemic Canada might have struggled to find resources for an athlete like Mitchell before Milton.

The 27-year-old Mitchell, from Sherwood Park, Alta., now lives in Milton and trains at the velodrome — officially called the Mattamy National Cycling Centre — with the rest of the sprint team, and will compete in the individual women’s race at the Games.

“We wouldn’t know what to do with that talent, right?” Harnett, Canada’s chef de mission in Brazil, said at a Milton event back in January 2020. “We wouldn’t have that capability to focus energy on that. Now we can do stuff like that.

“That’s going to start happening more and more.”

Canada’s best medal hopes on the track in Izu probably lie in the women’s events, including the sprint and team pursuit, but the lack of recent international competition, like many sports at these Games, means there’s still a lot of unknowns.

“All the riders are setting personal bests in training,” Westwood said. “We know we’re dialled in.

“We just don’t know what everybody else has been doing for the last 18 months.”

Milton might seem like a curious place for a velodrome on the surface, but the town stepped up when others were concerned about the post-Pan Am costs of running the facility.

And Westwood pointed out southern Ontario’s population gives Cycling Canada a massive catch basin of potential athletes.

“There is a clear and seamless pathway,” he said. “That pathway wouldn’t exist without having a facility as an anchor. There’s what, like eight million people within a 100-kilometre radius?

“That’s almost twice the population of New Zealand.”

The national program underwent a performance review in 2008, and it was clear to all involved a dedicated, year-round facility was crucial.

“(Former CEO Greg Mathieu) was able to twist some arms and make sure that became part of the Pan Am Games plan — and then it needed a home,” Westwood said. “It was originally supposed to be in Hamilton, but nobody in Hamilton wanted to take the risk.

“Ultimately it was Milton that put their hands up.”

And the national program is thankful it did.

“Municipalities, generally, are interested in hockey arenas and gymnasiums,” Westwood said.

“A velodrome is a pretty tough sell.”

Maybe so, but Canada is now expecting to reap the rewards for many years — and Olympics — to come.

Including here in Japan.

— With files from Gregory Strong.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Aug. 2, 2021.